If you saw a windowless concrete eight-story cuboid building perched improbably atop a 3,500-foot mountain, like a sentinel against the clear blue sky, you must be looking at Mt Umunhum in the Santa Cruz mountains. The Cube is visible from miles away and this mountain was opened up to the public only in 2017, almost four decades after being decommissioned as part of a US Air Force station that housed about 125 airmen and their families in its heyday.

After riding east on Hicks Road from the town of Los Gatos into the Sierra Azul Open Space Preserve, I turn right and pick up Mt Umunhum Road to begin my ascent of the eponymous mountain. It’s early morning and I have the mountain almost to myself. The motorcycle leans eagerly around the curves, appearing to enjoy the cold mountain air and the light fog almost as much as its rider.

I stop at the Bald Mountain parking area to enjoy the views of the valley and the Almaden reservoir far below. As it swirls around the mountain, the road finds the gaps between trees to reveal occasional views of the bizarre mountaintop with its anomalous cube.

The cube was part of an early warning system set up in 1957, eight years after the Soviets had detonated their first atomic bomb and on the same year they would usher in the Cold War by putting an unremarkable two-foot metallic orb called Sputnik into low Earth orbit, and a mere three years before they would detonate the world’s most powerful thermonuclear device over Novaya Zemlya—deep within the Arctic Circle—that could have inflicted third-degree burns upon a hapless herder more than a hundred miles away, had he picked just that moment to step outside to milk his fondest reindeer for his morning coffee.

This unlikely mountain was called upon to do duty for our national defense, against unrelenting Soviet progress and military prowess. An 85-foot tall and 60-foot wide concrete fortress was erected and a massive red-and-white 150-foot sweeping radar hoisted above to scan the foreboding western skies—five times a minute—anxiously looking for the first signs of the cataclysmic Red menace.

Meanwhile, the folks in the towns of Los Gatos and San Jose lived through the hedonistic Sixties reassured that their skies above were keenly watched while they partied below, even as their radios would bleep five times a minute and put a lousy dent on their Jimi Hendrix Experience!

There’s something surprisingly asymmetrical when riding a motorcycle: cornering. Taking a right corner is always much harder than taking a left one. When you ride on the right side of the road and prepare to take a left turn, your eyes can see further, and through the turn, because of the space afforded by the oncoming lane on your left. By picking the line early and making use of the full width of the road, a rider can execute left turns precisely, even if the corner tightens up faster than expected.

Right turns can be blind, since you cannot easily see through the corner while riding on the right side of the road, especially when a mountain side looms to your right. A mistake in judging a right turn can run the motorcycle wide enough to drift across the centerline and put it directly onto the path of oncoming vehicles. Right-handed riders might also be more inclined to rely on their right eye, which has a natural advantage on left turns but is almost useless on the right. Many motorcycle accidents happen on poorly-judged right turns.

Training your vision is essential to safe riding. You constantly watch the road surface for surprises conniving to unseat you. You must consciously look where you want to go and this can be quite disconcerting when cornering, for you must turn your head and almost look over your shoulder and through the corner to the far end of the curve, trusting your peripheral vision to watch the road immediately ahead.

I park the bike at the top and walk up to the unsightly cube that hides a dazzling—almost 360 degree—view of Silicon Valley, the mountains across the bay, and the dark ocean to the west.

As I walk around, I imagine a young bored Cold War airman in brown camouflages sitting inside that concrete cage in front of a deeply recessed green terminal with a fat click-etty keyboard, a smoldering filterless Camel with an inch-long-ash-tip dangling precipitously from the corner of his mouth. A half-eaten ham sandwich sits on a well-thumbed issue of Playboy on his desk as he languidly watches for that one sinister ping that would metamorphose into a squadron of long range Tu-95 Soviet bombers (NATO codename, “Bear”) carrying atomic bombs that would ruthlessly take out San Francisco, LA, Seattle, and Chicago in one single scorching orchestrated first-mover attack, sending half the continent instantly up to Jesus and making Communism the religion for the world… once all the dust had settled and St Peter’s Gate had fallen off its tired hinges.

Our twenty-something airman’s only job was to stop all this before it actually happened. Since that terminal radar blip never came, he probably kept smoking them Camels and putting away ham sandwiches until one day the bosses put him out to pasture down the mountain, so they might bring up a fresh set of keen eyes that would lock on to that unremitting green radar screen inside the blue darkness of the whopping concrete bunker… and take possession of the raggedy Playboy.

I ride back, mindful to avoid using the rear brakes going downhill, given the lighter load that drops the traction of the rear tire. I get back onto Hicks Road and continue to the town of Old Almaden.

Old Almaden was a mercury mine, the first of any kind in California, that had started operating even before the Gold Rush. It was named after Almaden in Spain, the world’s largest and most productive quicksilver mine and lived up to its christening by becoming the world’s second largest, producing over 70 million dollars of quicksilver over its lifetime—a fortune unmatched even by any gold mine in the state.

The earliest miners from Mexico and Spain were followed by English miners from Cornwall, with a history of mining going back to the Bronze Age. Later, Chinese immigrants worked the mines, the kitchen, and the laundry. New Almaden developed a Spanishtown and an Englishtown, but curiously no Chinatown. That San Jose had five, may have had something to do with it.

I pull into the grounds of the stately Casa Grande, a three-story brick, adobe, and wood structure, that was the palatial residence of the mine’s manager and is now a mining museum. It is closed, so I walk through a small gazebo by the side of the building to gaze at the landscaped gardens behind.

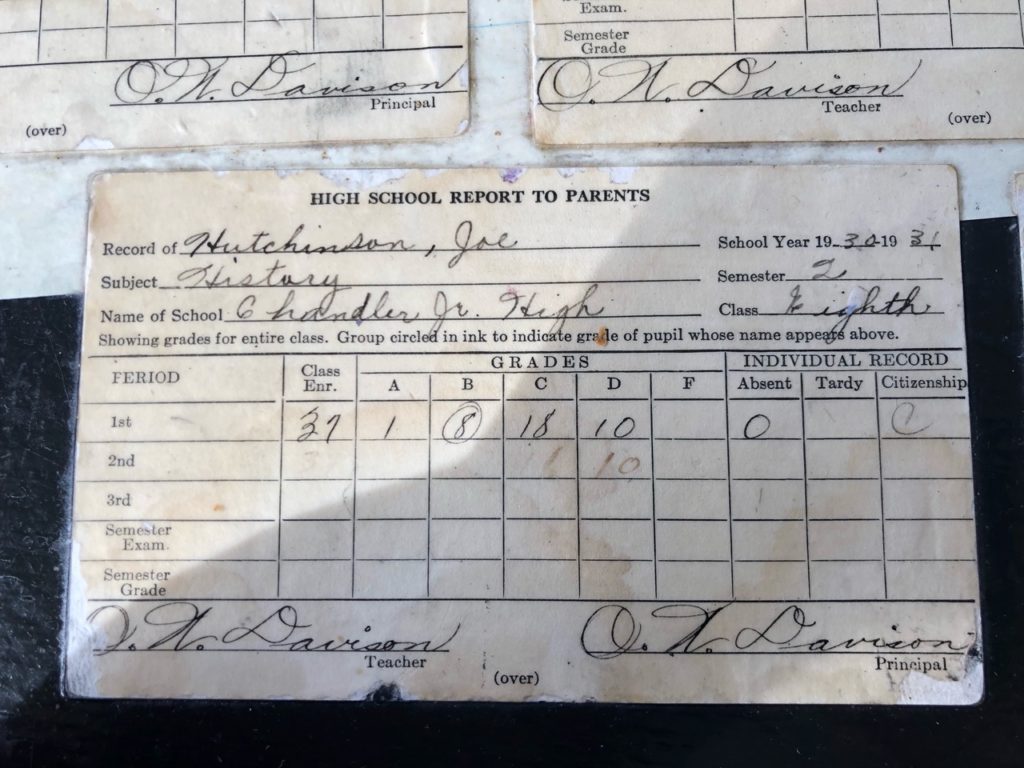

On my ride back, I stop for breakfast at the Blvd Cafe in San Jose. Working on a bagel with cream cheese and avocado, a laminated faded grade school report embossed on my tabletop catches my eye. It’s for Joe Hutchinson from Chandler Junior High—one of just eight students to secure a B in History in his eight grade class of thirty seven students.

The year?—1930! I wonder what ever happened to that studious Depression-era kid.