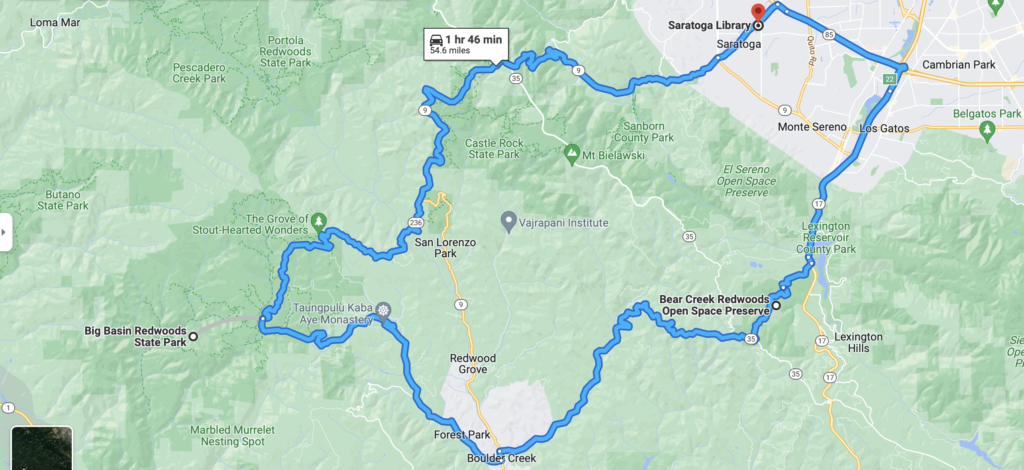

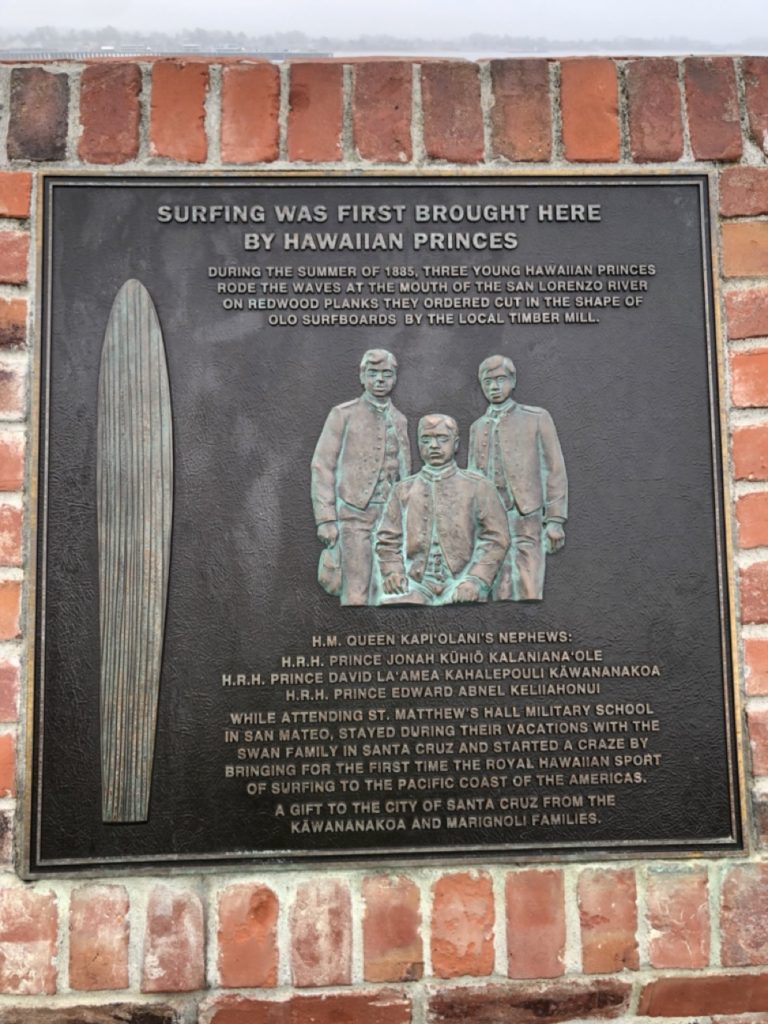

The Saratoga Gap is a mountain pass that has been used since the late 19th century to cross over the Santa Cruz mountains. The logging trail that descended from the crest of the mountains down to the towns of Saratoga and San Jose bearing redwood-laden wagons, is now a winding tar ribbon with aggressively banked curves, separated by short straights, that could put up g-forces normally found only on the racetrack. No surprise that on weekends, the mountains reverberate with the throaty roars of exotic sports cars and the banshee screams of barely street-legal motorcycles, as they pass brave bicyclists riding punishingly uphill for miles.

On an early Saturday morning, I reach the rim of the gap and ride on ahead onto Big Basin Way. Many miles later, I approach the junction where the road ahead had been closed for over two years to repair the devastation wreaked by the fire of 2020 upon the towering redwoods of the Big Basin State Park. That road-closed sign is gone today, so I continue straight ahead to visit the park through miles of tight curves—or twisties, as bikers like to call them.

Cars endure curves. Motorcycles crave them.

There’s damage everywhere—charred, browned, and stunted trees, amongst green ones—creating arid brown vistas in large sections that were verdant green. Some of these giants had lasted a thousand or more years of drought and fire, only to succumb to this one. I reach the state park without passing a single other vehicle and roll into the parking lot. A ranger sits disinterestedly in his cabin and I park the bike to take a stroll.

Walking around in protective motorcycle gear with a backpack and a helmet must be the closest modern approximation to a medieval knight in chainmail armor. Nothing is ever comfortable. Things conspire to poke you in unexpected places. You’re never sure if you’ll be around long enough, off the bike, to make it worth your while to pop off your lid.

If you do take off your helmet, you must cart it around until you can put it back on. If you leave it on, you feel about as out of place as a scuba diver at a nudist convention. Even if you attract any conversation, your ear-plugs will dutifully muffle it. You get unknowingly hotter, like that frog in the boiling water experiment. You want to scratch yourself in exactly the places where you cannot. To pee is no longer an urge, but a calculated deliberation. I do sometimes wonder if the ride is worth all this punishment.

But all this has given me new admiration for the knight in his pointy gear—the lance, the sword, the visor… the boot tips. How ever did he stumble through life without harrowingly poking his wretched groin?

But at least a knight had a squire. I don’t. I would have commissioned mine to help me off the bike, hold my helmet, and wheel the heavy bike into and out of parking spots. Perhaps he could even have cleaned and greased the drive chain, given his way with the metal stuff. Or brought me a hot masala chai and two pointy samosas.

I get back on the bike and ride past the park. Dangling limbs of dead trees gesticulate awkwardly in the sun. I ride for about half an hour until an intriguing roadway sign forces a stop. I park and see a hand-painted sign pointing to Pagoda and another to Monastery.

I’m at a monastery that was started by Taungpulu Sayadaw, a renowned Burmese forest monk of the most ancient Theravada tradition of Buddhism. There isn’t a soul anywhere. Perhaps they’ve been given up to Zoom. I leave the bike below and trudge up to the golden pagoda that looks lonely amidst the redwoods towering around it. Across the way, I see the monastery that’s supposed to hold a body relic of the venerable monk.

The road ends at Boulder Creek and I stop at the Tree House Cafe and put in for a coffee and a vege-burrito. The cafe is quirky and family-run and I notice how a massive redwood tree growing right through the roof has given the place its name. A pleasant girl at the counter takes my order, pronouncing my name perfectly. Turns out she has a friend with the same name.

I pick up the coffee and see an older woman sitting alone at a window table, lit brightly by the slanting rays of the morning sun. I ask to join her and she happily waves me in. We start up a conversation that would take up the next ninety minutes and last multiple rounds of coffee, meandering through children, grandchildren, mental health, spousal relationships, Mexico, Spain (she had a parent from each country), and the slumping real estate market. It’s amazing how strangers will divulge their personal stories and this always restores in me a fundamental faith in mankind.

Donning my gear again, I ride along Bear Creek Road and stop at a few interesting places where the sun trickles past the canopy to light up the forest floor in bright patches. I stop at the Bear Creek Nature Preserve about a dozen miles away that opened to the public a mere three years ago.

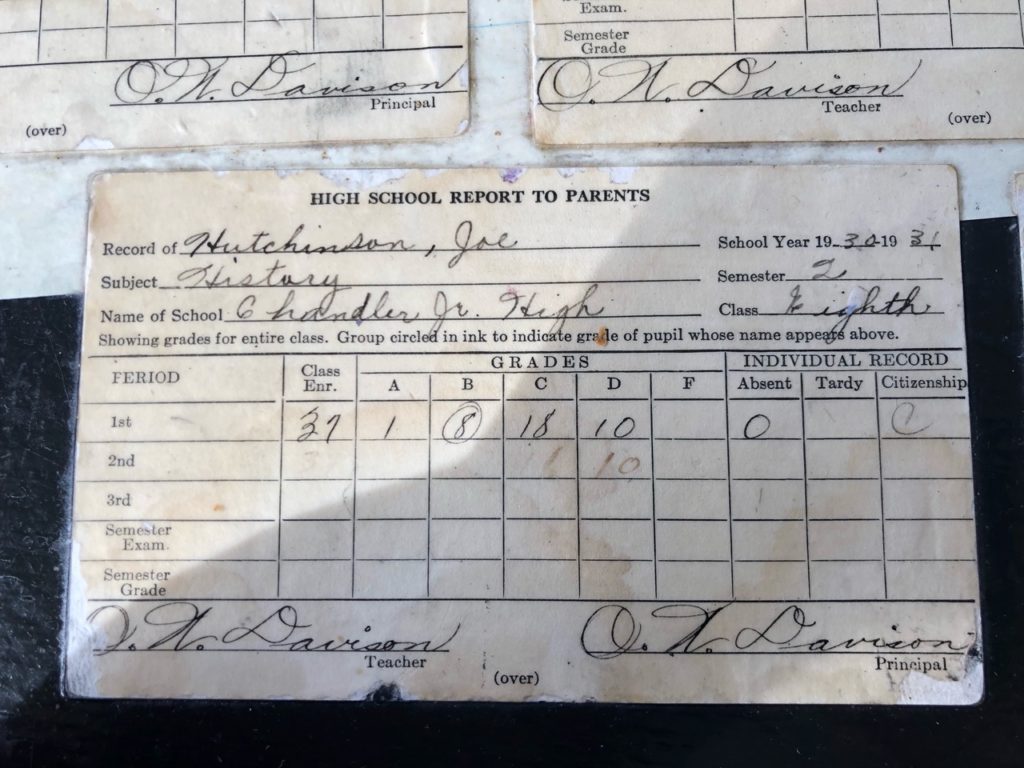

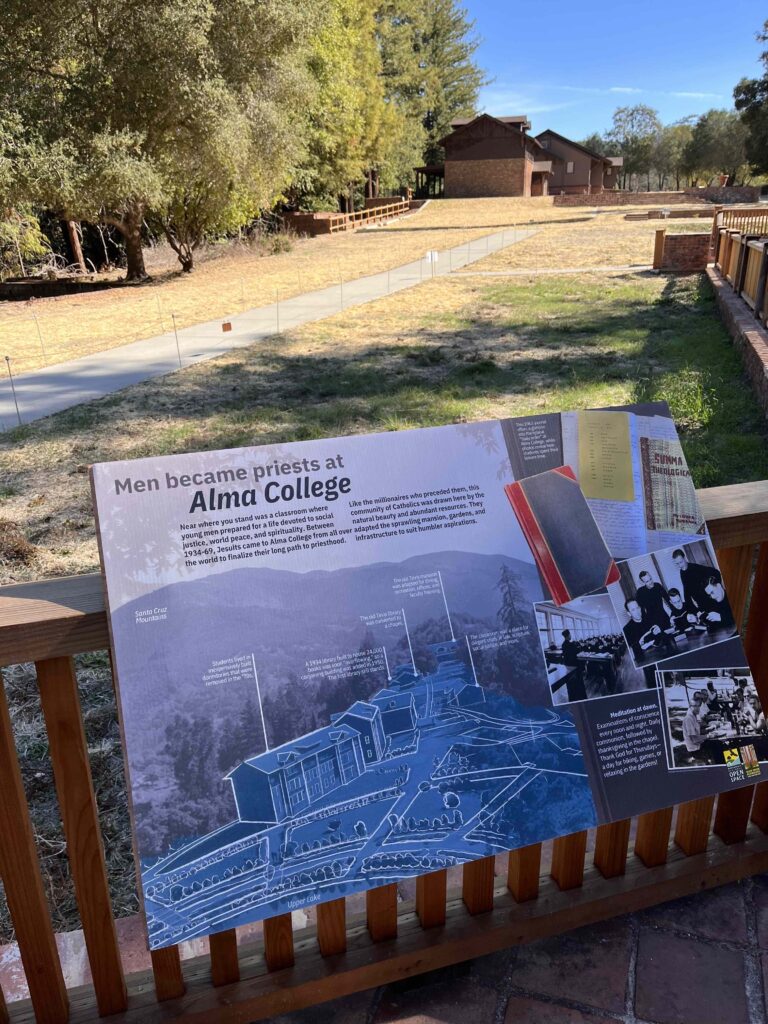

Across from the parking lot are the ruins of Alma College—one of only two Jesuit seminaries in the country—that was shut down in the late 1960s after decades of operation. I walk over to take a look at the buildings of the same theological order that founded my own high school in the mid 19th century, more than 10,000 miles away in Bangalore. I owe much of my foundational education to the tireless Jesuit fathers whose pedagogical methods included writing, memorization, and generous use of the wooden cane.

I wonder how my kids today would accept the profound explanation we were offered: Spare the rod and spoil the child.

I join Highway 17 and head towards Los Gatos. Unlike most exit ramps, the one for downtown Las Gatos is a straight one that comes up abruptly on the left. A motorist must exit here at high speed, yet slow down rapidly and sufficiently before they hit the first light at the heart of downtown to stop inches away from the unwary mom languidly pushing her stroller across the crosswalk. I downshift rapidly and perhaps too aggressively, for the bike shudders a bit but stays on course. For this dose of stability, I owe thanks to the slipper clutch.

A motorcycle clutch is a mechanical device that allows a running engine to be decoupled from the drive wheel—the rear one. You need this for a number of reasons, not the least of which is to be able to stop at a light, and if you were Peter Fonda, coolly smoke a cigarette while you waited. The clutch connects the engine, the drivetrain, and the rear wheel in a tight linkage that must be broken from time to time to get things done. An engaged clutch will disengage the engine, allowing it to spin freely and independently from the rear wheel, as during a gear change or at a light.

When a motorcycle is downshifted, the inertia of the rear wheel turns it faster than the engine, which is braking rapidly. By letting the clutch out slowly, the rider allows the clutch plates to slip against one another, so the extra momentum of the rear wheel is dissipated as friction at the clutch.

When a motorcycle is rapidly downshifted through multiple gears, the momentum of the rear wheel cannot find sufficient opposition from the clutch. Yet it must obey Sir Isaac Newton and find a way to dissipate that extra momentum. The easiest way out is for the wheel to lock up and slide out, causing what bikers call a lowside crash. A slipper clutch detects this back momentum and allows the clutch to automatically slip, without rider intervention, so the slack is taken up at the clutch rather than being forced at the wheel.

Technology wins and keeps the imprudent rider from parting with the bike.

As I head home, I see an older gentleman walking along with a grocery bag under each arm. I recognize him as my neighbor, but I can’t really stop the motorcycle and offer to pick him up, or his bags. I notice his car on the street when I get back and it hits me right then that Orthodox Jewish families don’t drive cars on Saturday, the Shabbat. I’ve lived across them for years and I can’t believe that I’ve never observed this until now.

So a bit of Buddhism, Catholicism, and Judaism conspired together to make my morning lovely. I feel privileged to live in a country where each can boldly thrive, but more importantly, motorcycles can roam free.